The accurate and timely diagnosis of disease is a prerequisite for efficient therapeutic intervention and epidemiological surveillance. Diagnostics based on the detection of nucleic acids are among the most sensitive and specific, yet most such assays require costly equipment and trained personnel. Recent developments in diagnostic technologies, in particular those leveraging clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), aim to enable accurate testing at home, at the point of care and in the field. In this Review, we provide a rundown of the rapidly expanding toolbox for CRISPR-based diagnostics, in particular the various assays, preamplification strategies and readouts, and highlight their main applications in the sensing of a wide range of molecular targets relevant to human health.

The fast and accurate diagnosis of a disease is central to effective treatment and to the prevention of long-term sequelae 1 . Nucleic-acid-based biomarkers associated with disease are essential for diagnostics because DNA and RNA can be amplified from trace amounts, which enables their highly specific detection via the pairing of complementary nucleotides. In fact, nucleic-acid-based diagnostics have become the gold standard for various acute and chronic conditions, especially those caused by infectious diseases 2 . During infectious-disease outbreaks, as most recently experienced with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, fast and precise nucleic-acid-based testing is vital for effective disease control 3,4 . The detection of nucleic acid biomarkers is also critical for agriculture and food safety, for environmental monitoring and in the sensing of biological warfare agents.

Nucleic acid-based diagnostics relying on the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or on sequencing have been widely adopted, and are frequently used in clinical laboratories. The versatility, robustness and sensitivity of PCR have made this technology the most commonly used for the detection of DNA and RNA biomarkers. In fact, PCR is the gold-standard technique for most nucleic-acid-based diagnostics. However, the costs of reagents for PCR are high, and the technique requires sophisticated laboratory equipment and trained personnel 5 . Although isothermal nucleic acid amplification circumvents the need for thermal cyclers, non-specific amplification can result in lower detection specificity 6 . The specificity can be improved through additional readouts, in particular by fluorescent probes 7 , oligo strand-displacement probes 8 or molecular beacons 9 . However, there is a need for technologies that combine the ease of use and cost efficiency of isothermal amplification with the diagnostic accuracy of PCR. Ideally, such next-generation diagnostics should also have single-nucleotide specificity, which is integral to the detection of mutations conferring resistance against antibiotics 10 or antiviral drugs 11 .

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based diagnostics have the potential to fulfil these unmet needs. CRISPR systems are a fundamental part of a microbial adaptive immune system 12 that recognizes foreign nucleic acids on the basis of their sequence to subsequently eliminate them by means of endonuclease activity associated with the CRISPR-associated (Cas) enzyme. Although there are diverse CRISPR–Cas systems among the different species of archaea and bacteria 13 , these systems are connected by their dependence on CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which guides Cas proteins to recognize and cleave nucleic acid targets. The crRNA can be programmed towards a specific DNA or RNA region of interest through hybridization to a complementary sequence, which in some systems is restricted to the proximity of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) or protospacer flanking sequence 14 . So far, CRISPR–Cas systems have been repurposed for a variety of applications, including the targeted editing of genomes 15 , epigenomes 16 and transcriptomes 17 , the bioimaging of nucleic acids 18 , the recording of cellular events 19 and the detection of nucleic acids. Overall, the fast-evolving area of CRISPR-based diagnostics builds on the specificity, programmability and ease of use of CRISPR technology, and aims to create nucleic-acid-based point-of-care (POC) diagnostic tests for use in routine clinical care.

In this Review, we outline how the properties of different Cas enzymes have been leveraged for diagnostic assays, discuss different preamplification strategies (which today form part of most CRISPR-based diagnostic assays), examine approaches for quantification and multiplexing, highlight technologies that combine CRISPR-based target enrichment with sequencing, and review the optimization of CRISPR-based diagnostics for POC applications, with a focus on assay readouts and sample preparation. We also provide an overview of the emerging biomedical applications of the technology, and discuss open challenges and opportunities.

Since their initial discovery, the number of different CRISPR–Cas systems has expanded rapidly 13,20,21 . Currently, CRISPR–Cas systems can be divided, according to evolutionary relationships, into two classes, six types and several subtypes 20 . The classes of CRISPR–Cas system are defined by the nature of the ribonucleoprotein effector complex: class 1 systems are characterized by a complex of multiple effector proteins, and class 2 systems encompass a single crRNA-binding protein. The design of crRNAs for the different effector proteins used in CRISPR diagnostics follow the same principles as those of other CRISPR applications, and are summarized in Table 1. Among the diverse CRISPR systems, class 2 systems have primarily been applied for diagnostics, as these systems are simpler to reconstitute. They include enzymes with collateral activity, which serves as the backbone of many CRISPR-based diagnostic assays (Table 2). Class 1 systems (such as the type III effector nuclease Csm6 or Cas10) have also been engineered for diagnostics, either in combination with components of the class 2 system or with the native type III complex 22,23 .

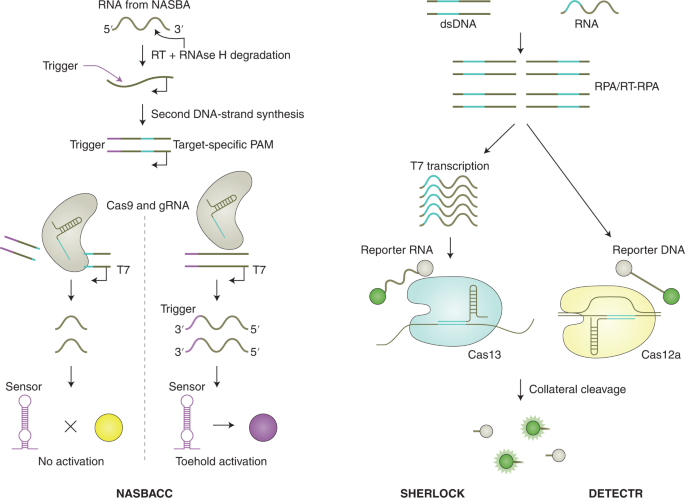

The main difference between CRISPR type II (Cas9) systems and type V (Cas12) and type VI (Cas13) systems is the ability of the latter two systems to trigger non-specific collateral cleavage (trans cleavage) on target recognition. Collateral activity involves the cleavage of non-targeted single-stranded DNA (ssDNA; Cas12) or single-stranded RNA (ssRNA; Cas13) in solution, which enables the sensing of nucleic acids through signal amplification and allows for various readouts through the addition of functionalized reporter nucleic acids, which are cleaved by collateral activity. The CRISPR–Cas type VI (Cas13) family of enzymes has a size range of ~900–1,300 amino acids, detects ssRNA in cis conformation and shows collateral trans-cleavage activity against ssRNA in vitro 30,31 . In the Cas13-based assay SHERLOCK (for specific high-sensitivity enzymatic reporter unlocking) 32 , DNA or RNA is first isothermally amplified with recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) 33 or reverse transcription RPA (RT-RPA), respectively, using a forward primer that adds a T7 promoter to the amplicon (Fig. 1, right). This promoter allows for RNA transcription of the target, which is then recognized and bound by a complex of Cas13a from Leptotrichia wadeii (LwaCas13a) and a crRNA that includes a complementary sequence to the target. The activated Cas13 will then cleave both the on-target RNA by cis cleavage and, in a target-dependent manner, the ssRNA reporter molecules by collateral trans cleavage. The ssRNA reporter molecules consist of a fluorophore and a quencher joined together by a short RNA oligomer, which, once cleaved, allows for the separation of the fluorophore from the quencher, resulting in fluorescence. These processes enable the detection of viral RNA, bacterial DNA, human single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and cancer-associated mutations with attomolar (10 –18 M) sensitivity. Version two of the assay (SHERLOCKv2) enabled the quantitative multiplexed sensing of nucleic acids and the target detection at zeptomolar (10 –21 M) concentrations, and introduced a lateral-flow readout based on an immunochromatographic assay, where cleaved reporter molecules are detected through antibody-conjugated gold nanoparticles on a paper strip 22,34 .

Cas12 enzymes that have been used in CRISPR-based diagnostics target dsDNA and ssDNA, require a PAM site in the target region for dsDNA cleavage and collaterally cleave ssDNA 35 . One of the first Cas12-based detection methods was reported in 2018 and referred to as DETECTR (for DNA endonuclease-targeted CRISPR trans reporter; Fig. 1, right) 36 . In this method, Cas12a from Lachnospiraceae bacterium (LbCas12a) or other organisms is guided to dsDNA targets by a complementary crRNA, triggering collateral cleavage of short ssDNA reporters carrying a fluorophore and a quencher. Similar to SHERLOCK, target recognition and reporter cleavage lead to the separation of the quencher from the fluorophore, which generates a fluorescence signal. DETECTR reached attomolar sensitivity when combined with RPA preamplification. Other Cas12-based techniques include HOLMES (for one-hour low-cost multipurpose highly efficient system) 37,38 , which employs PCR as preamplification together with LbCas12a, and HOLMESv2 39 , which uses loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) 40 combined with a thermostable Cas12b from Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris (AacCas12b) in a one-pot reaction. Both HOLMES and HOLMESv2 showed a limit of detection (LOD) around 10 aM. Similarly, Cas12f targets dsDNA and ssDNA, but enables better discrimination of SNPs in ssDNA than Cas12a 41 .

When using Cas enzymes without upstream preamplification of the target, most CRISPR-based diagnostics have a reported LOD in the picomolar range 32,42 . This LOD allows for target detection when there is a relatively high concentration of DNA or RNA in the sample. For example, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is apparently shed at high concentration in the early phase of infection (~6.76 × 10 5 copies per swab) 43 , allowing preamplification-free detection 44 . In addition to highly concentrated microbial samples, human genomic DNA (gDNA) 45 and highly expressed human messenger RNAs 30 and microRNAs (miRNAs) 46 have been reported to be amenable to detection without preamplification.

To increase the sensitivity of preamplification-free CRISPR-based diagnostics, LwaCas13a has been combined with the CRISPR type III RNA nuclease Csm6 22 . The nuclease activity of Csm6 is activated by cyclic oligoadenylates (2′,3′-cyclic phosphate groups) 47,48 . Because the collateral-cleavage activity of both LwaCas13a and PsmCas13b (from Prevotella sp. MA2016) generate products with hydroxylated 5′ ends and 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate ends, it was hypothesized that the collateral activity of Cas13 could generate Csm6 activators, thereby enabling amplified signal detection. In contrast to the cleavage preferences of LwaCas13a for the UU and AU two-base motifs, it was found that Csm6 from Enterococcus italicus (EiCsm6), Lactobacillus salivarius (LsCsm6) and Thermus thermophilus (TtCsm6) had strong cleavage preferences for A-rich and C-rich reporters, allowing for the cleavage activity of LwaCas13a and Csm6 to be independently measured in different channels and for the further design of ‘protected’ RNA activators. These activators were designed to contain a poly(A) Csm6 activator followed by a poly(U) stretch, on the basis of the rationale that the collateral cleavage of LwaCas13a would only degrade the uridines, thereby generating hexadenylates with 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate ends and activating Csm6. Activated Csm6 would in turn cleave additional reporter molecules, freeing up quenched fluorophores and thereby increasing the signal. This design led to a 3.5-fold increase in signal sensitivity when compared with Cas13a alone and when reading Csm6-mediated fluorescence and Cas13a-mediated fluorescence in the same channel. Similarly, the generation of cyclic oligoadenylates from the native Cas10 enzyme in type III systems has been used for detection of SARS-CoV-2 genomes 23 .

More strategies that increase the sensitivity of preamplification-free CRISPR-based diagnostics are needed. This could include the Cas-enzyme-mediated degradation of aptamers or of enzyme-inhibiting nucleic acid linkers (such as calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase or luciferase 49 ) that can then be detected via colorimetric or luminescence methods.

In contrast to applications that are amenable to preamplification-free CRISPR-based diagnostics, most clinical settings require the ability to sense nucleic acid concentrations below the picomolar range 50 . An example is the sensing of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) load under antiviral therapy 51,52 . Therefore, CRISPR-based diagnostics reported so far largely rely on the preamplification of the target. Although some studies use PCR 37,38 , isothermal amplification techniques are more compatible with POC use, owing to simpler instrumentation requirements (Table 3). Some of these methods function at near-ambient temperature (in particular, RPA, 37–42 °C), but others require heating devices (in particular, NASBA, 40–55 °C; LAMP, 60–65 °C; strand-displacement amplification 53 (SDA), 60 °C; helicase-dependent amplification 54 (HDA), 65 °C; and exponential amplification reaction 55 (EXPAR), 55 °C). In CRISPR-based diagnostics, the most commonly used isothermal amplification methods are RPA and LAMP. Initially, SHERLOCK 32 and DETECTR 36 used RPA for preamplification, which exhibited greater sensitivity than NASBA 32 . Although non-specific amplification represents a challenge in conventional RPA, the downstream crRNA-based target detection improves specificity. The design of RPA primers is less complex than the design of LAMP primers, but reliable procurement of the proprietary enzyme mix of a single supplier has been challenging. Furthermore, the addition of macromolecular crowding agents (such as poly(ethylene glycol)) together with low reaction temperatures reduces the mixing of the reagents and requires a mixing step for the amplification of lowly abundant targets 56 .

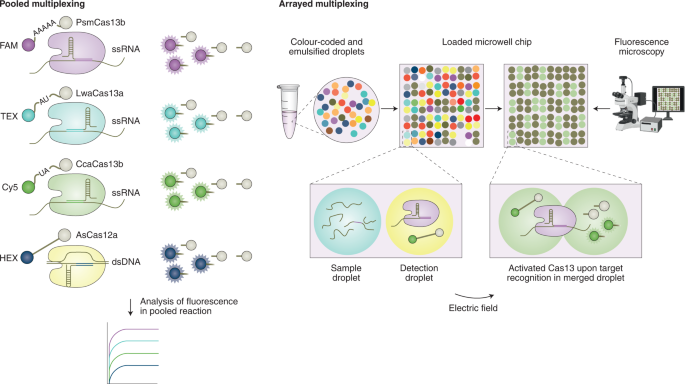

The CARMEN (for combinatorial arrayed reactions for multiplexed evaluation of nucleic acids) CRISPR-based multiplexed assay enables the scalable and parallel detection of more than 4,500 targets 67 . The method builds on the reaction chemistry of SHERLOCK, yet uses a miniaturized reaction volume (Fig. 2, right). In CARMEN, amplified nucleic acid target samples and LwaCas13 detection mixes are each combined with a distinct solution-based colour code. The colour-coded solutions are emulsified in fluorous oil, creating nanolitre droplet inputs. The droplets from all of the samples and detection mixes are pooled and subsequently loaded onto a microfabricated chip to create all possible pairwise combinations of sample and detection droplets (one pair per well). Droplet pairs are then merged by applying an external electric field. An initial recording of the dyes of two droplets in a particular microwell indicates which sample and detection droplet are present, and fluorescence generated through Cas13a-triggered reporter cleavage on target detection indicates a positive reaction. This miniaturization coupled with the high sensitivity and specificity of Cas13a enabled the detection of 169 human-associated viruses, the subtyping of coronaviruses and influenza A strains, and the identification of HIV mutations that are drug resistant. Compared with traditional DNA microarrays, CARMEN does not require the time-consuming spotting of probes and offers higher scalability than PCR panels. Although it requires a preamplification step, microscopy analysis and skilled lab personnel, CARMEN allows for fast, high-throughput and low-cost pathogen detection, which is critically needed in clinical routines and for the surveillance of emerging public-health threats. Owing to the miniaturized reactions for detection, CARMEN considerably reduces reagent costs and sample consumption. However, its current dependence on advanced microscopy limits the use of the technology to resource-rich laboratory settings.

Because sequencing-based diagnostic technologies use the alignment of reads to bioinformatic databases for pathogen identification, they tolerate variability in the genome of the target organism and do not necessarily require prior knowledge of the target sequence. These features are particularly useful when the pathogen is unknown, or when its genome evolves quickly. However, to detect low-abundance pathogens, the enrichment of regions of interest before sequencing becomes necessary. PCR-based amplification of sequencing regions has several limitations, including the removal of epigenetic marks, amplification bias and challenges associated with the amplification of GC-rich regions or of very large regions. Larger amplicons are of particular interest for long-read sequencing techniques, such as nanopore sequencing, because they allow for the characterization of long-range structural variations.

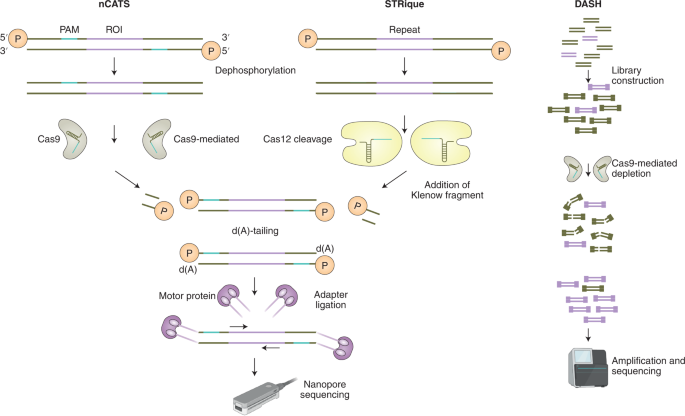

To overcome these limitations, several protocols use Cas nucleases to enrich regions of interest before sequencing. For example, nanopore Cas9-targeted sequencing (nCATS) uses Cas9 to cleave chromosomal DNA for the ligation of adapters for nanopore sequencing (Fig. 3, left), enabling the targeted sequencing of long fragments at high depth while maintaining epigenetic marks 68 . This technology allowed the simultaneous detection of CpG methylation, structural variations and haplotype-resolved single-nucleotide variants using 3 μg of genomic DNA, and it achieved 675× coverage with a MinION flow cell and 34× coverage with the Flongle flow cell (both cells are commercialized by Oxford Nanopore Technologies). In a similar effort to circumvent the need for PCR-based enrichment, STRique (for short tandem repeat identification, quantification and evaluation) was developed 69 for the identification of short tandem repeats (STRs) with nanopore sequencing (Fig. 3, left). In addition to Cas9, Cas12a was used to induce DNA cuts next to a repeat-containing region, followed by the ligation of adapters for nanopore sequencing. Using an algorithm that identified the positions of the STR-flanking regions and the number of STRs between them, the method enabled the detection of STR expansion alongside CpG methylation status in cell lines derived from patients with fragile X syndrome and with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

CRISPR–Cas systems have also been combined with targeted next-generation sequencing to increase the sequencing yield. For example, DASH (for depletion of abundant sequences by hybridization) was developed 70 to enrich pathogen sequences and to remove unwanted species. In this method, a library of crRNAs directs Cas9 to unwanted target sequences for cleavage, and non-targeted regions retain the intact adapters required for amplification and sequencing (Fig. 3, right). Another method, FLASH (for finding low-abundance sequences by hybridization), includes the blocking of gDNA by phosphatase and digestion through Cas9 complexed to a set of crRNAs targeting genes of interest, followed by the ligation of adapters, and by amplification and sequencing 71 . This technique detected, in respiratory fluids and dried blood spots, subattomolar levels of drug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria and the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

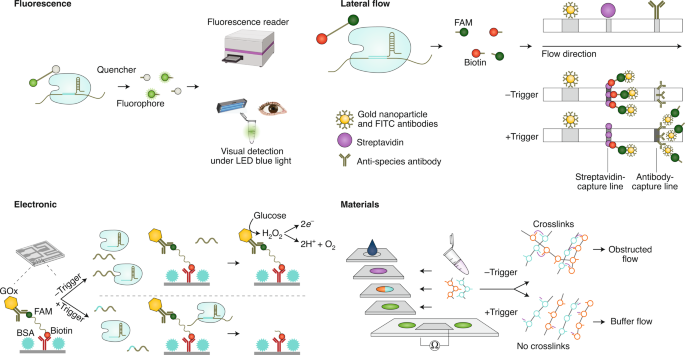

Some strategies for measuring and visualizing the activation of Cas enzymes on target recognition have employed fast and low-cost readouts amenable for POC or field applications. The usage of reporter molecules with different properties enables a wide variety of readouts, including fluorescence, lateral-flow immunochromatography and electrochemistry. For fluorescence-based assays, most CRISPR-based diagnostic methods take advantage of RNA or DNA reporter molecules carrying a fluorophore and a quencher. Collateral-cleavage activity on target detection causes the spatial separation of the fluorophore and the quencher, and the resulting fluorescence can be read on conventional plate readers (Fig. 4, top left), on low-cost and portable devices 72 and even with the naked eye under blue light 60 (Fig. 4, top left). Additional strategies enable colorimetric visualization by using gold nanoparticles, which are linked through ssRNA or ssDNA oligonucleotides. Cas12-mediated or Cas13-mediated trans cleavage of the linker resulted in the dispersal of the gold nanoparticles on target recognition, and produced a vibrant red colour in solution 73 . Alternatively, Cas-mediated cleavage of biotinylated ssDNA substrates resulted in a decrease in the magnetic pull-down of DNA gold nanoparticles 74 . A turbidity-based assay based on the liquid–liquid phase separation of nucleic acids and positively charged polyelectrolytes can also provide visual readouts 75 . In this case, collateral cleavage leads to the degradation of nucleic acid polymers on target recognition. This can be visualized after complementation with polycations, where the solution either stays clear when cleavage has occurred or becomes turbid in the absence of target-triggered cleavage.

Lateral-flow assays (Fig. 4, top right) offer a simple visualization of the collateral cleavage activity inherent to many CRISPR-based diagnostics. A commercially available system (Millenia 1T) first reported in ref. 22 has been widely adopted. In this technique, reporter molecules carrying biotin and fluorescein (fluorescein amidite (FAM)) bind to anti-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) antibodies coupled to gold nanoparticles in the sample pad area of the strip. These complexes subsequently travel to a streptavidin-capture line, where they bind through the biotin of the reporter molecule. In the absence of the target, uncut reporter molecules are retained there, and this is visualized as one band on the strip. In the presence of the target, Cas-enzyme-mediated collateral cleavage of the reporter separates the biotin from the FAM molecules bound to the anti-FITC gold nanoparticles, allowing them to travel farther on the strip and generating a second visible band at the antibody-capture line, which bears species-specific secondary antibodies. An alternative to collateral cleavage-based target detection combines Cas9-based amplicon detection with a lateral-flow readout using a crRNA-anchoring-based hybridization assay 76 .

CRISPR-based diagnostics with electronic readouts are also possible. One method, named CRISPR–Chip, involved deactivated Cas9 complexed with a target-specific crRNA and immobilized on a graphene-based field-effect transistor 45 . On target binding, alterations to graphene’s conductivity caused the electrical properties of the transistor to change, which can be measured as a change in current. Notably, this technology did not require labelled reporter molecules and could sense deletions in the dystrophin gene in unamplified gDNA samples from patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. The sensitivity of the system reached the femtomolar range (~1.7 fM). Another strategy for obtaining electronic readouts, named E-CRISPR, involved an ssDNA-cleavage reporter with a methylene blue electrochemical tag and a thiol moiety for immobilization on a gold electrode 77 . In this method, Cas12a-mediated collateral cleavage upon target detection led to a decrease in the electrochemical current through the release of methylene blue, whereas the absence of target resulted in a high electrochemical current, owing to an intact methylene blue-carrying reporter. This assay detected human papillomavirus and parvovirus B19 DNA with a LOD of ~50 pM, and can be adapted for protein sensing. Another method used an electrochemical biosensor to detect Cas13a-mediated collateral cleavage of RNA reporters carrying FAM and biotin 46 (Fig. 4, bottom left). In this approach, the binding of glucose-oxidase-coupled anti-FAM antibodies to reporter molecules immobilized on the sensor catalysed the oxidation of glucose. The produced H2O2 was then amperometrically detected by using an electrochemical cell with a platinum working electrode, a platinum counter electrode and a silver/silver chloride reference electrode. This technique allowed the detection of miRNAs at a LOD of 10 pM within 4 hours in volumes smaller than 0.6 μl (this LOD was achieved using a separate ‘off-chip’ cleavage; the all-in-one sensor had a LOD of 2.2 nM). Cas13a-based electrochemical detection of miRNAs was also shown with a portable electrochemiluminescence chip 78 (with a reported limit of detection of 1 fM). In this technique, the miRNA-mediated activation of Cas13a led to the collateral cleavage of a trigger for the initiation of exponential isothermal amplification. The amplified products formed a complex with [Ru(phenanthroline)2dipyridophenazine] 2+ , and the oxidation of the complex at the anode of a bipolar electrode generated an electrochemiluminescent signal proportional to the concentration of the target miRNA.

DNA hydrogels have been designed to enable CRISPR-based diagnostic readouts through changes in their material property 79,80 . The hydrogels consist of water-filled polymers containing DNA molecules serving as an anchor or structural element within the gel (Fig. 4, bottom right). On target recognition, Cas12a triggers collateral cleavage of the DNA molecules, which changes the properties of the gel. This technology was used for sensing pathogen-derived nucleic acids in a multilayered paper-based microfluidic device (μPAD) with dual visual and electronic readouts. In the absence of the target, the DNA-linker-containing hydrogel obstructed the flow of a buffer through the porous channels of the paper-based device. Target recognition led to Cas12a-mediated linker destruction, which prevented hydrogel crosslinking and caused visually observable flow through the porous μPAD channels. This technique allowed for the detection of dsDNA down to 400 pM without preamplification. To create an electronic readout, two electrodes were placed in the bottom layer of the μPAD. Because the electrical conductivity of the gel depended on its degree of crosslinking, low levels of crosslinking due to Cas12a-mediated cleavage caused an electrolyte-containing buffer to flow, whereas high levels of crosslinking in the absence of any target blocked the buffer from flowing through, thereby preventing the recording of an electric signal. Moreover, the incorporation of a wireless radiofrequency identification (RFID) module into the μPAD enabled the monitoring of target detection at different geographic locations in real time. To this end, Cas12a-mediated collateral cleavage on target detection resulted in the short-circuiting of an interdigitated electrode arrangement in the loop RFID tag, which increased the strength of the received signal with respect to that of a reference RFID tag.

Sample processing is a critically important consideration for improving the usability of CRISPR-based diagnostics for field applications and POC settings. CRISPR-based diagnostics initially used synthetic targets or time-consuming or equipment-intensive nucleic acid isolation protocols. More recent efforts aim for the rapid and equipment-free isolation of DNA or RNA. Importantly, the reagents used in the sample-extraction steps must not interfere with any downstream preamplification steps or with CRISPR-based target detection. As in many cases, the final readout is based on collateral-cleavage activity, and special precautions must be taken to ensure the absence of RNases and DNases, which can cleave ssRNA or ssDNA reporters.

The original SHERLOCK protocol showed that saliva could be processed directly by using 0.2% Triton X-100 in a lysis mixture with phosphate buffered saline, and by heating at 95 °C for 5 min. This crude saliva mixture was used in a SHERLOCK reaction for genotyping. To expand to additional sample types, the protocol HUDSON (for heating unextracted diagnostic samples to obliterate nucleases) enabled the inactivation of nucleases and viruses through heat and chemical reduction through the addition of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride at a 100 mM final concentration and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) at a 1 mM final concentration 81 . Different heating steps (ranging from 5 min to 20 min and from 37 °C to 95 °C) were optimized for different targets and sample types. HUDSON enabled the detection of RPA-preamplified targets through CRISPR–Cas13a, including the sensing of ZIKV and dengue virus in blood, plasma, serum, saliva and urine. Since the HUDSON protocol was not sufficient to inactivate nucleases for the detection of Plasmodium species (as observed by the fraction of false-positive samples), a preparation buffer containing stronger chelating agents has been developed (20% w/v Chelex100 TE-buffer containing dithiothreitol (DTT) at 50 mM) 61 .

A commercially available fast DNA-extraction solution (QuickExtract, Lucigen) enables fast RNA preparation for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA through RT–qPCR 82 . Here nasopharyngeal swabs are mixed with the extraction solution, incubated at 95 °C for 5 min and directly used in the RT–qPCR reaction after cool down. This isolation protocol is compatible with downstream RT-LAMP preamplification and detection through Cas12b from Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus (AapCas12b) 63 . QuickExtract also enabled the lysis of samples at 22 °C or 60 °C for 10 min, and when proteinase K was blocked in the downstream reactions by an inhibitor.

One advantage of CRISPR-based diagnostic assays is their independence from complex and costly laboratory equipment and from common reagents such as PCR master mixes. Because Cas enzymes and crRNAs can be produced fast and at scale, CRISPR-based assays are less dependent on supply-chain issues. However, although the costs of buffers, primers and the oligos used as templates for crRNA synthesis are negligible, CRISPR-based assays include many more enzymes than PCR, especially when an isothermal preamplification step is included. The cost for an individual CRISPR-based diagnostics reaction with preamplification is approximately US$0.61 per reaction in an experimental setting 32 . Of these costs, RPA reagents made up the largest fraction. However, the first commercially available CRISPR-based diagnostic assay for SARS-CoV-2 including RT-LAMP as preamplification is currently available at US$30.15 per reaction (https://www.idtdna.com/pages/landing/coronavirus-research-reagents/sherlock-kits). It is unclear how prices will develop after the approval of more tests, and how patents that cover methods for the sensing of nucleic acids through CRISPR–Cas proteins will affect the dissemination of the technology.

Most CRISPR-based diagnostic assays use liquid reagents, which afford experimental flexibility. However, the storage of solutions of the crRNA, cleavage reporter and Cas protein typically requires freezers that maintain ultralow temperatures. Lyophilization of these components and of the preamplification reagents eliminates the dependence on cold chains, and by using higher input volumes of sample the assay sensitivities can be similar 31 or even higher 61 than with the use of non-lyophilized reactions. Systematic stability testing of the components for CRISPR-based diagnostics is needed, yet studies in clinical cohorts 83 and the assessment of daily experimental variation 84 suggest that the results of the assays are highly reproducible.

CRISPR-based diagnostics have been used for a wide range of biomedical applications, and in particular for the sensing of nucleic-acid-based biomarkers of infectious and non-infectious diseases and for the detection of mutations and deletions indicative of genetic diseases. Moreover, the technology has been adapted for the sensing of proteins and small molecules.

The main focus of CRISPR-based diagnostics has been the detection of pathogens; in particular, the DNA or RNA of viruses, bacteria and parasites. RNA viruses sensed with CRISPR-based methods include parvovirus B19 (ref. 77 ), members of the family Flaviviridae (dengue 22,25,81 , Zika 25,32 and Japanese encephalitis virus 37 ), Ebola 85 and Coronaviridae (which have naturally become a major focus of interest during the COVID-19 pandemic).

The SHERLOCK-based detection of SARS-CoV-2 initially consisted of a two-step assay comprising RPA-based preamplification, followed by T7 transcription and Cas13a-mediated target recognition 86 . This assay has been tested in a qPCR-validated clinical cohort containing 154 samples analysed by lateral-flow and fluorescence readouts, and with 380 PCR-negative samples analysed by fluorescence only 83 . The assay reached a LOD of 42 RNA copies per reaction, and sensitivities of 96% and 88% when using fluorescence and lateral-flow readouts, respectively. Both readouts were 100% specific. In May 2020, a modified SHERLOCK-based two-step assay using RT-LAMP instead of RT-RPA received emergency use authorization from the United States Food and Drug Administration for the CRISPR-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Testing with this assay is intended for the qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 in specimens of the upper respiratory track, and is limited to laboratories authorized by CLIA (for clinical laboratory improvement amendments) regulations. A different Cas13a-based assay, SHINE (for SHERLOCK and HUDSON integration to navigate epidemics) 62 , combined the preamplification reaction and CRISPR-based detection into a single-step reaction that uses HUDSON to accelerate SARS-CoV-2 viral extraction in nasal swabs and saliva samples. The addition of RNase H, the optimization of buffers, concentrations of magnesium and of primers, and the usage of a polyU reporter together with a SuperScript-IV reverse transcriptase, reduced the LOD to a range similar to that of the two-step assay (10 copies per μl with the fluorescent readout, and 100 copies per μl with the lateral-flow readout). The test was validated on 50 nasopharyngeal patient samples, and achieved 90% sensitivity and 100% specificity against RT–PCR. In a different Cas13-based approach, the integration of multiple crRNAs, the usage of a Cas13a homologue from Leptotrichia buccalis (Lbu) and the measurement of fluorescence over time enabled the detection of SARS-Cov-2 RNA extracted from nasal swabs down to 1.27 × 10 8 copies per ml (1.65 × 10 3 copies per μl in the Cas13 reaction). Importantly, this was achieved without the need for preamplification, and the assay was compatible with readout using a portable fluorescence-detection device 44 .

By using Cas12a, the two-step assay SARS-CoV-2 DETECTR was optimized to detect the N (nucleoprotein) and E (envelope small membrane protein) genes of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, as well as a human control gene (for the ribonuclease P protein), in less than 40 min from respiratory swab RNA extracts preamplified by RT-LAMP 87 . SARS-CoV-2 DETECTR returned results with a 95% positive predictive agreement and a 100% negative predictive agreement relative to the RT–qPCR assay from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cas12a was also used in the SARS-CoV-2 AIOD-CRISPR (for all-in-one dual CRISPR–Cas12a) assay 60 , which uses Cas12a together with a pair of non-PAM-dependent crRNAs, each sensing separate regions of the target nucleic acid amplicon. These Cas12a-crRNA complexes were introduced into a one-pot assay containing the reagents for RPA-based preamplification and the cleavage reporter. This approach enabled the detection of 5 copies of synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA per reaction, and was validated in 28 clinical swab samples. STOPCovid (for SHERLOCK testing in one pot) 63 , another Cas12-based one-pot assay, integrated RT-LAMP-based preamplification with CRISPR-mediated detection in a one-step workflow. Of the various Cas proteins explored, Cas12b from Alicyclobacillus acidiphilus (AapCas12b) together with the scaffold single guide RNA from AacCas12b, allowed the test to run at the temperature range required for LAMP. STOPCovid has a sensitivity comparable to that of RT–qPCR, with a LOD of 100 copies of viral genome per reaction.

Besides RNA viruses, DNA viruses such as Herpesviridae (including cytomegalovirus (CMV) 84 and Epstein–Barr virus 88 ), Polyomaviridae (BK virus (BKV)) 84 and Papillomaviridae (human papillomavirus) 36 have also been detected with CRISPR-based diagnostics. In particular, a SHERLOCK-based assay was used to detect CMV and BKV in a clinical setting 84 .The assay was validated with qPCR, and detected BKV from 67 HUDSON-isolated plasma and urine samples with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity. HUDSON-based processing of CMV-containing plasma samples resulted in 80% sensitivity and 100% specificity, whereas DNA purification through silica-based membranes was necessary to reach 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity. To objectively assess the results of the lateral-flow assay, a smartphone-based software application was developed to quantify band intensities. The background signal of the lateral-flow assay was independent of daily experimental variation, incubation time and temperature, which facilitated the reproducibility of the qualitative readout.

Bacteria detected with CRISPR include Mycobacterium tuberculosis 32,89 , Staphylococcus aureus 22,32,90 , Listeria monocytogenes 91 , Pseudomonas aeruginosa 32 and Salmonella enteritidis 92 . CRISPR has also been adapted to sense the parasites of the Plasmodium group responsible for malaria. This includes the sensing of different P. falciparum strains 71 and the development of a pan-plasmodium assay 93 that detected all Plasmodium species known to cause malaria in humans as well as the species-specific detection of P. vivax and P. falciparum. A different CRISPR-based assay based on an RPA–Cas12a one-pot reaction using lyophilized reagents downstream of a simplified sample preparation was developed for the detection of P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale and P. malariae 61 . The addition of a reverse transcriptase to transcribe target RNA into DNA increased the assay’s sensitivity. The protocol achieved a LOD between 0.36 and 2.4 parasites per μl, depending on the Plasmodium species.

CRISPR-based diagnostics have also been developed for the detection of RNA species relevant to non-infectious diseases. For example, CRISPR-based sensing of human CXCL9 mRNA was used to detect acute cellular kidney-transplant rejection, as defined by renal biopsy, with a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 76%, in total RNA isolated from 31 urinary cell pellets 84 . CRISPR-based diagnostics have also been used to sense miRNAs, as exemplified by the CRISPR/LwaCas13a-based electrochemical detection of miR-19b in serum samples of patients with medulloblastoma 46 without preamplification, and the testing of RNA isolated from breast cancer cell lines for miR-17 with CRISPR/LbuCas13a 94 and for miR-21 with LbCas12a, after rolling-circle transcription 95 .

A major strength of CRISPR-based diagnostics is the single-nucleotide specificity of Cas enzymes, which enables the detection of point mutations and small deletions. Single-nucleotide specificity has made possible the CRISPR-based detection of markers of antimicrobial resistance, of deletions and mutations in the epidermal-growth-factor-receptor gene 22 , of mutations conferring Duchenne muscular dystrophy 45 and of SNPs in the E3 ubiquitin ligase gene conferring eye colour 41 . The single-nucleotide specificity of the CRISPR–Cas system has also been leveraged for the sensing of miRNAs, which are challenging to detect because of their short size and because they can differ by only a single base. CRISPR-based approaches may also be suitable for the detection of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants that might differ in pathogenicity and transmissibility 96 .

CRISPR-based diagnostic methods have been adapted for the detection of proteins and small molecules. In these cases, the CRISPR system is primarily used as a reporter or amplifier, and the actual sensing of the target molecule is mediated through proteins or aptamers that undergo a conformational change on target recognition. One strategy for sensing small molecules combined CRISPR–Cas12a with bacterial allosteric transcription factors 97 (aTFs). Referred to as CaT-SMelor (for CRISPR–Cas12a-mediated and aTF-mediated small molecule detector), the method was applied to sense uric acid and p-hydroxybenzoic acid at nanomolar concentrations, and thereby enabled the detection of uric acid in human blood samples. In this method, the incubation of immobilized aTF–dsDNA complexes containing the Cas12a target sequence with the aTF target small molecule led to a conformational change in the aTF that freed the dsDNA from the complex. After removal of the immobilized aTF by centrifugation, free dsDNA was detected using CRISPR–Cas12a and measured through the collateral cleavage of a quenched fluorescent reporter. SPRINT (for SHERLOCK-based profiling of in vitro transcription) 98 used aTFs and riboswitches that are triggered by specific effector molecules to regulate transcription of RNA targets. Transcribed RNA is then detected by a crRNA and Cas13a. This enabled the sensing of a wide range of effector molecules (including fluoride, adenine, guanine, S-adenosylmethionine, flavin mononucleotide, serotonin, zinc and anhydrotetracycline).

A different approach to sensing small molecules involved an aptamer that contained an ssDNA target of Cas12a, which served as a sensor for adenosine triphosphate 99 (ATP; reported LOD of the assay, 400 nM of ATP). In this approach, the binding of ATP to the aptamer hindered target recognition and thereby reduced the Cas12a-triggered collateral cleavage of an ssDNA reporter. Alternatively, ATP or Na + ions have been sensed through aptamers or DNAzymes (also referred to as ‘functional DNA’) that release Cas12a targets on binding to their non-nucleic acid targets, resulting in the activation of Cas12a as detected by the trans cleavage of fluorescent reporter molecules 100 .

Similarly, an aptamer-based detection method has been developed for the CRISPR–Cas12a-based sensing of the transforming growth factor β1 (TGF‐β1) protein 77 . In this method, TGF-β1 binds to a specific ssDNA aptamer that contains a Cas12a target site. In the absence of TGF-β1, all free and unbound aptamer molecules are recognized by Cas12a, whose collateral-cleavage activity of ssDNA reporters that carry methylene blue results in a decrease of the electrochemical signal, which is sensed by E-CRISPR. The aptamer-based E-CRISPR assay allowed for the detection of TGF-β1 in clinical samples with a LOD of 0.2 nM. And CLISA (for CRISPR–Cas13a-based signal amplification linked immunosorbent assay) was developed to sense human interleukin-6 at 2.29 fM and human vascular endothelial growth factor at 0.81 fM (ref. 101 ). This was achieved by replacing the signal-amplification enzyme of a sandwich-type enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (using horseradish peroxidase) with biotinylated dsDNA containing a T7 promoter, which allowed T7-mediated transcription of a Cas13a target, leading to its activation and to the collateral cleavage of a reporter.

In less than five years, CRISPR-based diagnostics have evolved from an experimental nucleic acid sensing tool to a clinically relevant diagnostic technology for the fast, affordable and ultrasensitive sensing of biomarkers at the POC. However, there are several challenges that the technology needs to overcome to be able to deliver on the promise of transforming the way diseases are diagnosed and emerging pathogens monitored. A major shortcoming of most current CRISPR-based diagnostics is their dependence on preamplification for the detection of targets below the femtomolar range. Although the primers used for preamplification add another layer of specificity, this process adds complexity to the assay, increases its costs and prolongs the reaction time. The incorporation of non-primer-based signal-amplification strategies, or modifications of the Cas enzyme, crRNA or reporter molecule, are potential paths for improvement. Currently, most crRNAs and primers for preamplification have to be experimentally tested, and the design rules to narrow down potential candidates are coarse. Machine learning and bioinformatics algorithms based on large-scale experimental datasets could allow for the development of more effective design tools for the better prediction of crRNA performance and for improving crRNA specificity and activity. In fact, the feasibility of such approaches for crRNA design has been shown in the context of genome engineering 102,103 and in the characterization and optimization of toehold switches 104,105 .

The ease of use of CRISPR-based diagnostics has been improved through optimized one-pot reactions and the simple visualization of test results. However, sample preparation still requires a separate step, and incubation temperatures higher than room temperature necessitate heating devices. In addition, target concentrations close to the LOD of the assay make it challenging to quantify the readout with certainty, especially when using the lateral-flow format. For usage at home or in the field, the assay design should combine simple sample-preparation protocols with robust detection methods to deliver robust results in variable or challenging contexts, such as prolonged storage, limited user training and harsh environmental conditions. To this end, devices that integrate sample preparation, sensing and reporting in single and easy-to-operate units are increasingly possible by using microfluidic techniques 106 . And the combination of such devices with digital analysis and data-sharing systems holds promise for patient-centric testing and remote data access. This is particularly important for mitigating the spread of infectious diseases by limiting unnecessary in-person contact in hospitals. Also, CRISPR-based diagnostics may enable patient-centric companion nucleic-acid-based diagnostics for monitoring treatment responses to a drug and to differentiate patients that are at risk for serious adverse effects from those that will probably benefit from the drug 107 . CRISPR-based diagnostics could facilitate the monitoring of genetic markers indicative of treatment response, such as mutations in the BRAF gene, which are commonly used to inform the treatment of melanoma skin cancer 108 . Furthermore, CRISPR-based diagnostics may be used for the real-time monitoring of gene expression across different tissues through the sensing of cell-free mRNA 109 .

Future applications of CRISPR-based diagnostics will probably involve technologies at the intersection with materials science 79,80 , for the sensing of nucleic acids on solid surfaces, on wearables and on medical devices. For example, ongoing work aims to incorporate SARS-CoV-2 sensors into face masks for the real-time detection of the virus. Direct sensing on surfaces can take advantage of high local concentrations of infectious agents and could allow for continuous tracking and for early diagnosis. This could extend the capabilities of monitoring strategies, such as the use of toilet systems for the analysis of excreta 110 .

Newly developed CRISPR assays must, of course, be validated 83 by clinical trials, and assay validity monitored and maintained after clinical implementation. Yet, we believe that rapid innovation in CRISPR-based diagnostics will end up reshaping the technological landscape of nucleic-acid-based detection.

M.M.K. was supported by the Emmy Noether Programme (KA5060/1-1) of the German Research Foundation (DFG). J.J.C. was supported by the Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group and the Wyss Institute. All figures were created with BioRender.com.