freeCodeCamp

![Command Line for Beginners – How to Use the Terminal Like a Pro [Full Handbook]](https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/content/images/size/w2000/2022/03/pexels-pixabay-207580.jpg)

By Germán Cocca

Hi everyone! In this article we'll take a good look at the command line (also known as the CLI, console, terminal or shell).

The command line is one of the most useful and efficient tools we have as developers and as computer users in general. But using it can feel a bit overwhelming and complex when you're starting out.

In this article I'll try my best to simply explain the parts that make up the command line interface, and the basics of how it works, so you can start using it for your daily tasks.

I think a good place to start is to know exactly what the command line is.

When referring to this, you may have heard the terms Terminal, console, command line, CLI, and shell. People often use these words interchangeably but the truth is they're actually different things.

Differentiating each isn't necesarilly crucial knwoledge to have, but it will help clarify things. So lets briefly explain each one.

The console is the physical device that allows you to interact with the computer.

In plain English, it's your computer screen, keyboard, and mouse. As a user, you interact with your computer through your console.

A terminal is a text input and output environment. It is a program that acts as a wrapper and allows us to enter commands that the computer processes.

In plain English again, it's the "window" in which you enter the actual commands your computer will process.

Keep in mind the terminal is a program, just like any other. And like any program, you can install it and uninstall it as you please. It's also possible to have many terminals installed in your computer and run whichever you want whenever you want.

All operating systems come with a default terminal installed, but there are many options out there to choose from, each with its own functionalities and features.

A shell is a program that acts as command-line interpreter. It processes commands and outputs the results. It interprets and processes the commands entered by the user.

Same as the terminal, the shell is a program that comes by default in all operating systems, but can also be installed and uninstalled by the user.

Different shells come with different syntax and characteristics as well. It's also possible to have many shells installed at your computer and run each one whenever you want.

In most Linux and Mac operating systems the default shell is Bash. While on Windows it's Powershell. Some other common examples of shells are Zsh and Fish.

Shells work also as programming languages, in the sense that with them we can build scripts to make our computer execute a certain task. Scripts are nothing more than a series of instructions (commands) that we can save on a file and later on execute whenever we want.

We'll take a look at scripts later on in this article. For now just keep in mind that the shell is the program your computer uses to "understand" and execute your commands, and that you can also use it to program tasks.

Also keep in mind that the terminal is the program in which the shell will run. But both programs are independent. That means, I can have any shell run on any terminal. There's no dependance between both programs in that sense.

The CLI is the interface in which we enter commands for the computer to process. In plain English once again, it's the space in which you enter the commands the computer will process.

This is practically the same as the terminal and in my opinion these terms can be used interchangeably.

One interesting thing to mention here is that most operating systems have two different types of interfaces:

We just mentioned that most operating systems come with a GUI. So if we can see things on the screen and click around to do whatever we want, you might wonder why you should learn this complicated terminal/cli/shell thing?

The first reason is that for many tasks, it's just more efficient. We'll see some examples in a second, but there are many tasks where a GUI would require many clicks around different windows. But on the CLI these tasks can be executed with a single command.

In this sense, being comfortable with the command line will help you save time and be able to execute your tasks quicker.

The second reason is that by using commands you can easily automate tasks. As previously mentioned, we can build scripts with our shell and later on execute those scripts whenever we want. This is incredibly useful when dealing with repetitive tasks that we don't want to do over and over again.

Just to give some examples, we could build a script that creates a new online repo for us, or that creates a certain infrastructure on a cloud provider for us, or that executes a simpler task like changing our screen wallpaper every hour.

Scripting is a great way to save up time with repetitive tasks.

The third reason is that sometimes the CLI will be the only way in which we'll be able to interact with a computer. Take, for example, the case when you would need to interact with a cloud platform server. In most of these cases, you won't have a GUI available, just a CLI to run commands in.

So being comfortable with the CLI will allow you to interact with computers on all ocassions.

The last reason is it looks cool and it's fun. You don't see movie hackers clicking around their computers, right? ;)

Before diving into the actual commands you can run in your terminal, I think it's important to recognize the different types of shells out there and how to identify which shell you're currently running.

Different shells come with different syntax and different features, so to know exactly what command to enter, you first need to know what shell you're running.

For shells, there's a common standard called Posix.

Posix works for shells in a very similar way that ECMAScript works for JavaScript. It's a standard that dictates certain characteristics and features that all shells should comply with.

This standard was stablished in the 1980's and most current shells were developed according to that standard. That's why most shells share similar syntax and similar features.

To know what shell you're currently running, just open your terminal and enter echo $0 . This will print the current running program name, which in this case is the actual shell.

There's not A LOT of difference between most shells. Since most of them comply with the same standard, you'll find that most of them work similarly.

There are some slight differences you might want to know, though:

The fact that shells add more features makes them easier and friendlier to interact with, but slower to execute scripts and commands.

So a common practice is to use this "enhanced" shells like Bash or Zsh for general interaction, and a "stripped" shell like Ash or Dash to execute scripts.

When we get to scripting later on, we'll see how we can define what shell will execute a given script.

If you're interested in a more detailed comparison between these shells, here's a video that explains it really well:

If had to recommend a shell, I would recommend bash as it's the most standard and commonly-used one. This means you'll be able to translate your knowledge into most environments.

But again, truth is there's not A LOT of difference between most shells. So in any case you can try a few and see which one you like best. ;)

I just mentioned that Fish comes with built-in configuration such as autocompletion and syntax highlighting. This come built-in in Fish, but in Bash or Zsh you can configure these features, too.

The point is that shells are customizable. You can edit how the program works, what commands you have available, what information your prompt shows, and more.

We won't see customization options in detail here, but know that when you install a shell in your computer, certain files will be created on your system. Later on you can edit those files to customize your program.

Also, there are many plugins available online that allow you to customize your shell in an easier way. You just install them and get the features that plugin offers. Some examples are OhMyZsh and Starship.

These customization options are also true for Terminals.

So not only do you have many shell and terminal options to choose from – you also have many configuration options for each shell and terminal.

If you're starting out, all this information can feel a bit overwhelming. But just know that there are many options available, and each option can be customized too. That's it.

Now that we have a foundation of how the CLI works, let's dive into the most useful commands you can start to use for your daily tasks.

Keep in mind that these examples will be based on my current configuration (Bash on a Linux OS). But most commands should apply to most configurations anyway.

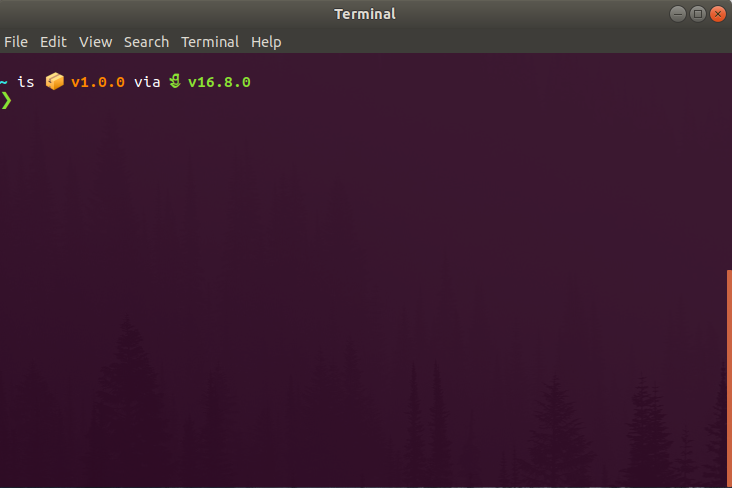

echo Hello freeCodeCamp! // Output: Hello freeCodeCamp! pwd // Output: /home/German For example, here I'm on a React project directory I've been working on lately:

ls // Output: node_modules package.json package-lock.json public README.md src If you pass this command the flag or paremter -a It will also show you hidden files or directories. Like .git or .gitignore files

ls -a // Output: . .env .gitignore package.json public src .. .git node_modules package-lock.json README.md While on my home directory, I can enter cd Desktop and it will take me to the Desktop Directory.

If I want to go up one directory, meaning go to the directory that contains the current directory, I can enter cd ..

If you enter cd alone, it will take you straight to your home directory.

If I wanted to create a new directory called "Test" I would enter mkdir test .

If I want to make a copy of my txt file in the same directory, I can enter the following:

cp test.txt testCopy.txt See that the directory doesn't change, as for "destination" I enter the new name of the file.

If I wanted to copy the file into a diferent directory, but keep the same file name, I can enter this:

cp test.txt ./testFolder/ And if I wanted to copy to a different folder changing the field name, of course I can enter this:

cp test.txt ./testFolder/testCopy.txt Again, this command takes two paremers, the file or directory we want to move and the destination.

mv test.txt ./testFolder/ We can change the name of the file too in the same command if we want to:

mv test.txt ./testFolder/testCopy.txt head test.txt // Output: this is the beginning of my test file this is the end of my test file

- The **--help** flag can be used on most commands and it will return info on how to use that given command.

cd --help // output: cd: cd [-L|[-P [-e]] [-@]] [dir] Change the shell working directory.

Change the current directory to DIR. The default DIR is the value of the HOME shell variable. The variable CDPATH defines the search path for the directory containing DIR. Alternative directory names in CDPATH are separated by a colon `:`. A null directory name is the same as the current directory if DIR begins with `. `. - In a similar way, the **man** command will return info about any particular command. CP(1) User Commands CP(1)

NAME cp - copy files and directories

SYNOPSIS cp [OPTION]. [-T] SOURCE DEST cp [OPTION]. SOURCE. DIRECTORY cp [OPTION]. -t DIRECTORY SOURCE.

DESCRIPTION Copy SOURCE to DEST, or multiple SOURCE(s) to DIRECTORY.

Mandatory arguments to long options are mandatory for short options too.

-a, --archive same as -dR --preserve=all

--attributes-only don't copy the file data, just the attributes .

You can even enter `man bash` and that will return a huge manual about everything there's to know about this shell. ;) - **code** will open your default code editor. If you enter the command alone, it just opens the editor with the latest file/directory you opened. You can also open a given file by passing it as parameter: `code test.txt`. Or open a new file by passing the new file name: `code thisIsAJsFile.js`. - **edit** will open text files on your default command line text editor (which if you're on Mac or Linux will likely be either Nano or Vim). If you open your file and then can't exit your editor, first look at this meme:  And then type `:q!` and hit enter. The meme is funny because everyone struggles with CLI text editors at first, as most actions (like exiting the editor) are done with keyboard shortcuts. Using these editors is a whole other topic, so go look for tutorials if you're interested in learning more. ;) - **ctrl+c** allows you to exit the current process the terminal is running. For example, if you're creating a react app with `npx create-react-app` and want to cancel the build at some point, just hit **ctrl+c** and it will stop. - Copying text from the terminal can be done with **ctrl+shift+c** and pasting can be done with **ctrl+shift+v** - **clear** will clear your terminal from all previous content. - **exit** will close your terminal and (this is not a command but it's cool too) **ctrl+alt+t** will open a new terminal for you. - By pressing **up and down keys** you can navigate through the previous commands you entered. - By hitting **tab** you will get autocompletion based on the text you've written so far. By hitting **tab twice** you'll get suggestions based on the text you've written so far. For example if I write `edit test` and **tab twice**, I get `testFolder/ test.txt`. If I write `edit test.` and hit **tab** my text autocompletes to `edit test.txt` ## Git commands Besides working around the file system and installing/uninstalling things, interacting with Git and online repos is probably the most common things you're going to use the terminal for as a developer. It's a whole lot more efficient to do it from the terminal than by clicking around, so let's take a look at the most useful git commands out there. - **git init** will create a new local repository for you.

git init // output: Initialized empty Git repository in /home/German/Desktop/testFolder/.git/

- **git add** adds one or more files to staging. You can either detail a specific file to add to staging or add all changed files by typing `git add .` - **git commit** commits your changes to the repository. Commits must always be must be accompanied by the `-m` flag and commit message.

git commit -m 'This is a test commit' // output: [master (root-commit) 6101dfe] This is a test commit 1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-) create mode 100644 test.js

- **git status** tells you what branch are you currently on and whether you have changes to commit or not.

git status // output: On branch master nothing to commit, working tree clean

- **git clone** allows you to clone (copy) a repository into the directory you're currently in. Keep in mind you can clone both remote repositories (in GitHub, GitLab, and so on) and local repositories (those that are stored in your computer).

git clone https://github.com/coccagerman/MazeGenerator.git // output: Cloning into 'MazeGenerator'. remote: Enumerating objects: 15, done. remote: Counting objects: 100% (15/15), done. remote: Compressing objects: 100% (15/15), done. remote: Total 15 (delta 1), reused 11 (delta 0), pack-reused 0 Unpacking objects: 100% (15/15), done.

- **git remote add origin** is used to detail the URL of the remote repository you're going to use for your project. In case you'd like to change it at some point, you can do it by using the command `git remote set-url origin`.

git remote add origin https://github.com/coccagerman/testRepo.git

> Keep in mind you need to create your remote repo first in order to get its URL. We'll see how you can do this from the command line with a little script later on. ;) - **git remote -v** lets you list the current remote repository you're using.

git remote -v // output: origin https://github.com/coccagerman/testRepo.git (fetch) origin https://github.com/coccagerman/testRepo.git (push)

- **git push** uploads your commited changes to your remote repo.

git push // output: Counting objects: 2, done. Delta compression using up to 8 threads. Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done. Writing objects: 100% (2/2), 266 bytes | 266.00 KiB/s, done. Total 2 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

- **git branch** lists all the available branches on your repo and tells you what branch you're currently on. If you want to create a new branch, you just have to add the new branch name as parameter like `git branch `.

git branch // output:

git checkout newBranch // output: Switched to branch 'newBranch' If there's new code in your remote repo, the command will return the actual files that were modified in the pull. If not, we get Already up to date .

git pull // output: Already up to date. git diff newBranch // output: diff --git a/newFileInNewBranch.js b/newFileInNewBranch.js deleted file mode 100644 index e69de29..0000000 As a side comment, when comparing differences between branches or repos, ussually visual tools like Meld are used. It's not that you can't visualize it directly in the terminal, but this tools are greate for a clearer visualization.

git merge newBranch // output: Updating f15cf51..3a3d62f Fast-forward newFileInNewBranch.js | 0 1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-) create mode 100644 newFileInNewBranch.js git log // output: commit 3a3d62fe7cea7c09403c048e971a5172459d0948 (HEAD -> main, tag: TestTag, origin/main, newBranch) Author: German Cocca Date: Fri Apr 1 18:48:20 2022 -0300 Added new file commit f15cf515dd3ec398210108dce092debf26ff9e12 Author: German Cocca . git diff --help // output: GIT-DIFF(1) Git Manual GIT-DIFF(1) NAME git-diff - Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc SYNOPSIS git diff [options] [] [--] [. ] git diff [options] --cached [] [--] [. ] . Now we're ready to get to the truly fun and awesome part of the command line, scripting!

As I mentioned previously, a script is nothing more than a series of commands or instructions that we can execute at any given time. To explain how we can code one, we'll use a simple example that will allow us to create a github repo by running a single command. ;)

This is called a shebang, and its function is to declare what shell is going to run this script.

Remember previously when we mentioned that we can use a given shell for general interaction and another given shell for executing a script? Well, the shebang is the instruction that dictates what shell runs the script.

As mentioned too, we're using a "stripped down" shell (also known as sh shells) to run the scripts as they're more efficient (though the difference might be unnoticeable to be honest, It's just a personal preference). In my computer I have dash as my sh shell.

If we wanted this script to run with bash the shebang would be #! /bin/bash

Here we're declaring a variable called repoName, and assigning it to the value of the first parameter the script receives.

A parameter is a set of characters that is entered after the script/comand. Like with the cd command, we need to specify a directory parameter in order to change directory (ie: cd testFolder ).

A way we can identify parameters within a script is by using dollar sign and the order in which that parameter is expected.

If I'm expecting more than one parameter I could write:

paramOne=$1 paramTwo=$2 paramThree=$3 . We can do that like this:

while [ -z "$repoName" ] do echo 'Provide a repository name' read -r -p $'Repository name:' repoName done What we're doing here is: 1) While the repoName variable is not assigned ( while [ -z "$repoName" ] ) 2) Write to the console this message ( echo 'Provide a repository name' ) 3) Then read whatever input the user provides and assign the input to the repoName variable ( read -r -p $'Repository name:' repoName )

echo "# $repoName" >> README.md git init git add . git commit -m "First commit" This is creating a readme file and writting a single line with the repo name ( echo "# $repoName" >> README.md ) and then initializing the git repo and making a first commit.

curl is a command to transfer data from or to a server, using one of the many supported protocols.

Next we're using the -u flag to declare the user we're creating the repo for ( -u coccagerman ).

Next comes the endpoint provided by the GitHub API ( https://api.github.com/user/repos )

And last we're using the -d flag to pass parameters to this command. In this case we're indicating the repository name (for which we're using our repoName variable) and setting private option to false , since we want our repo to be puiblic.

Lots of other config options are available in the API, so check the docs for more info.

If you don't have a private token yet, you can generate it in GitHub in Settings > Developer settings > Personal access tokens

To get that we're going to use curl and the GitHub API again, like this:

GIT_URL=$(curl -H "Accept: application/vnd.github.v3+json" https://api.github.com/repos/coccagerman/"$repoName" | jq -r '.clone_url') Here we're declaring a variable called GIT_URL and assigning it to whatever the following command returns.

The -H flag sets the header of our request.

Then we pass the GitHub API endpoint, which should contain our user name and repo name ( https://api.github.com/repos/coccagerman/"$repoName" ).

Then we're piping the return value of our request. Piping just means passing the return value of a process as the input value of another process. We can do it with the | symbol like | .

And finally we run the jq command, which is a tool for processing JSON inputs. Here we tell it to get the value of .clone_url which is where our remote git URL will be according to the data format provided by the GitHub API.

git branch -M main git remote add origin $GIT_URL git push -u origin main Our full script should look something like this:

#! /bin/sh repoName=$1 while [ -z "$repoName" ] do echo 'Provide a repository name' read -r -p $'Repository name:' repoName done echo "# $repoName" >> README.md git init git add . git commit -m "First commit" curl -u https://api.github.com/user/repos -d '' GIT_URL=$(curl -H "Accept: application/vnd.github.v3+json" https://api.github.com/repos//"$repoName" | jq -r '.clone_url') git branch -M main git remote add origin $GIT_URL git push -u origin main One option is to enter the shell name and pass the file as parameter, like: dash ../ger/code/projects/scripts/newGhRepo.sh .

And the other is to make the file executable by running chmod u+x ../ger/code/projects/scripts/newGhRepo.sh .

Then you can just execute the file directly by running ../ger/code/projects/scripts/newGhRepo.sh .

And that's it! We have our script up and running. Everytime we need a new repo we can just execute this script from whatever directory we're in.

But there's something a bit annoying about this. We need to remember the exact route of the script directory. Wouldn't it be cool to execute the script with a single command that it's always the same independently of what directory we're at?

In come bash aliases to solve our problem.

Aliases are a way bash provides for making names for exact commands we want to run.

To create a new alias, we need to edit the bash configuration files in our system. This files are normally located in the home directory. Aliases can be defined in different files (mainly .bashrc or .bash_aliases ).

I have a .bash_aliases file on my system, so let's edit that.

Here I'm declaring the alias name, the actual command I'm going to enter to run the script ( newghrepo ).

And between quotes, define what that alias is going to do ( "dash /home/German/Desktop/ger/code/projects/scripts/newGhRepo.sh" )

See that I'm passing the absolute path of the script, so that this command works the same no matter what my current directory is.

If you don't know what the absolute path of your script is, go to the script directory on your terminal and enter readlink -f newGhRepo.sh . That should return the full path for you. ;)

I hope this gives you a little taste of the kind of optimizations that are possible with scripting. It certainly requires a bit more work the first time you write, test, and set up the script. But after that, you'll never have to perform that task manually again. ;)

The terminal can feel like an intimidating and intricate place when you're starting out. But it's certainly worth it to put time and effort into learning the ins and outs of it. The efficiency benefits are too good to pass up!

If you're interested in learning more about the terminal and Bash, Zach Gollwitzer has an awesome crash course series on youtube. He has also great tutorials on other topics such as Node and Javascript, so I recommend that you follow him. ;)

As always, I hope you enjoyed the article and learned something new. If you want, you can also follow me on linkedin or twitter.

Cheers and see you in the next one! =D